|

|

|

|

|

|

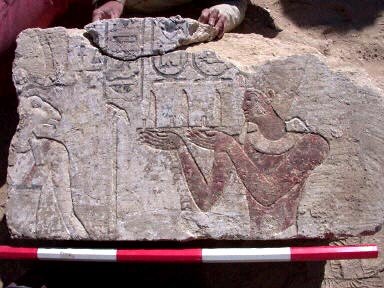

Pharaonic temple discovered in Egypt's desert

Archaeologists

have discovered the ruins of a Pharaonic temple in Egypt's western desert

that will help their knowledge of oases in ancient times. "Now

destroyed and buried in sand in the middle of the desert, this temple

which was about 20 metres (66 feet) long is located 140 kilometres (85

miles) from Siwa on the banks of an ancient abandoned oasis," Italian

Egyptologist Paolo Gallo said. "The

major deities of the Egyptian pantheon are represented in very beautiful

painted relief" on blocks from the collapsed walls of the temple,

Gallo said. His

mission is working to save the most important blocks, which are threatened

by erosion due to the region's strong winds. The

oldest part of the temple was built and decorated by the Pharaoh Nectanebo

I (380-361 BC), said Gallo, of the archaeological mission of Turin

University. "Thanks

to the hieroglyphic inscriptions at the site, we have been able to

identify the name which the oasis was given in antiquity: Imespep,"

he said. "This

find is of considerable historical importance," the archaeologist

said, pointing out that it was the first known monument of Nectanebo I in

the Siwa region. Gallo

explained that the find "reveals the political will of this ruler to

develop the zone of the western oases of Egypt and improve the caravan

links with the Nile Valley".

|

The

site itself was uncovered in the 1920s in the oasis called nowadays

Bahrein, which means in Arabic the two seas, or lakes. "But the

existence of this temple was not known at all", he said. "The

sanctuary was dedicated to a special cult of the god Amun, who was called

here 'Amun who gives strength'," said the archaeologist. Next

to the temple, a hall supported by six pillars was added to the sanctuary,

probably under the Ptolemies (323-30 BC). Bahrein,

or Imespep, was in antiquity a caravan city on the road between the oasis

of Bahariya to the oasis of Siwa, both of which are still populated. It lies in an area of the western desert called the Great Sand Sea because of gigantic dunes under which the lost army of Persian emperor Cambyses is said to be buried. Herodotus,

the leading source of original information about the history of Greece and

Egypt between 550 and 479 BC, said Cambyses' 50,000 strong army vanished

there on their way to plunder Siwa. Cambyses

invaded Egypt in 525, overthrowing the native Egyptian pharaoh Psamtek

III, last ruler of Egypt's 26th Dynasty, to become the first ruler of

Egypt's 27th Persian Dynasty. Gallo

said Bahrein was deserted in Byzantine times (395-640 AD) as caravan

traffic declined, and was never populated again because the region is one

of the world's most hostile places for people to live. Gallo

created in 1997 the Italian Archaeological Mission of Alexandria (CMAIA)

which is also working on Nelson island, off the coast of the Mediterranean

city. It

discovered there last November the remains of a Macedonian fortress built

by settlers who came with Alexander the Great.

|

|

What JewBus, Unitarian Pagans, and the Hot Tub

Mystery Religion tell us about traditional faiths. By Jesse Walker There is a group

in the Dallas area called the Hot Tub Mystery Religion. Its adherents hold

to no particular spiritual dogma, borrowing freely from such sources as

Jewish mysticism, Roman paganism, Islamic heresy, and experimental art.

One of its founders has compiled a recommended reading list for the

faithful; it includes a collection of Tantric exercises, a text on Sufism,

one of Philip K. Dick’s Gnostic science fiction stories, and a novel by

the Catholic apologist G.K. Chesterton. The group has been known to treat

nitrous oxide as a sacrament and to throw Jacuzzi parties -- hence the

name. In raw numbers,

the Hottubbists constitute one of the smallest religions in the world:

With well under 100 practitioners, it is dwarfed even by Rastafarianism

and Scientology. The group is interesting for many reasons, but its social

influence is not among them. Though small and

obscure, it is an example of a significant social trend: the blurring

boundaries between art and faith. Atheists have long regarded religion as,

at best, a collective work of art, but in the last century that view has

grown popular with churchgoers as well. Many Christians and Jews today

will declare that the Bible is a collection of myths and metaphors, not

literal truths, and some will aver that there is more than one path to

God. Neopagans and others take this nonliteral and eclectic approach and

run with it, freely fusing classical mythologies, tribal spiritual

practices, and even popular fiction, all of which would be mutually

exclusive if they were regarded as, to borrow a phrase, the Gospel truth.

At the far end of the spectrum are those who do not merely regard religion

as a human creation but actively identify themselves as its creators. The

Hot Tub group actually began as an art project, becoming a more spiritual

endeavor only gradually. If it is unusual, it is only because it is so

radical. Most people do not feel the need to be the authors of their own

religions, though quite a few are happy to be the editors. Whether this is

bad or good depends on your attitude toward orthodoxy. Traditionalists

often castigate what they call the spiritual cafeteria, in which ordinary

worshippers pick and choose the beliefs and practices that appeal to them,

customizing their faiths to fit their lifestyles instead of altering their

lives to fit the dictates of their denominations. The cafeteria line

includes every Catholic who casually dissents from the edicts of Rome,

every otherwise observant Jew who eats food made in nonkosher kitchens,

every Muslim who adjusts his prayer schedule to his workday rather than

the other way around. Sometimes, these pickers and choosers even mix in

their favorite features of other faiths. Some think the

most important religious trend today is a rise in fundamentalism; others,

a rise in disbelief. But somewhere between those two phenomena, another

interesting evolution is taking place. A large slice of the American

public, many of them card-carrying members of mainline denominations, are

living spiritual lives that are customized, eclectic, and otherwise

comparable to those found in the Hot Tub church. Customized

Doctrine Few issues seem

more settled than the Vatican’s position on abortion. The pope campaigns

constantly against the practice, and the institution he heads has arguably

done more for the fetal cause than any other group. The church’s

catechism -- in its own words, "the essential and fundamental

contents of Catholic doctrine" -- declares, "Human life must be

respected and protected absolutely from the moment of conception. From the

first moment of his existence, a human being must be recognized as having

the rights of a person -- among which is the inviolable right of every

innocent being to life." So the first

thing you might think, upon learning of a 30-year-old lobby called

Catholics for a Free Choice (CFFC), is that its very premise is a paradox,

comparable to Vegetarians for Veal or Maoists for the Preservation of

Property Rights. Frances Kissling, the group’s president since 1982,

would disagree. "I have a good understanding of what I’m required

to believe and accept as a Catholic," she says, "and I know that

within the Catholic tradition, I have the right to dissent from even

serious but non-infallible teachings. Abortion, women’s ordination,

family planning, married male priests, homosexuality: All these areas of

controversy are open to disagreements." Pressed, she offers a

detailed argument, part history and part theology, that the Catholic

position on whether and when a fetus might be a person has varied

considerably over the last two millennia. I’m not

competent to judge Kissling’s theological position, and I’m not about

to try. Her foes, however, have not been so wary. Magaly Llaguno,

co-author of a tract titled Catholics for a Free Choice Exposed,

has accused her of remaining in the church only "to sow discord and

division." Speaking in Toronto in 1999, Llaguno said Kissling’s

group "is, in my opinion, usurping and misusing the term Catholic.

Perhaps the Vatican and the bishops in each individual country in the

world should copyright this term, so CFFC cannot continue to use it." Yet Kissling not

only embraces the Catholic label but sees herself as part of a proud Roman

tradition. She is a Catholic, not a Protestant, because something in

Catholicism appeals to her. "There are parts of me that do say,

‘Give it up, go someplace friendlier,’" she confesses. "But

religious faith is not a matter of rationality. There’s a part of my

life, my spirit, that is irrational, and Catholicism appeals to

that." She admires Catholicism’s elaborate theology, its rich

intellectual history, its support for humanitarian causes, even its music.

("I prefer Catholic Gregorian chants to Buddhist chants.")

"It’s partly cultural," she explains. "This is a religion

I grew up with. I lived the first 20 years of my life in a largely

Catholic community. Who I am -- my values, how I see the world, my

imagination -- was formed by Catholicism. In the same way that I love

myself, I love that which formed me." Kissling adds

that "even an excommunicated Catholic is a Catholic," which

might strike even liberal clergy as going too far. Thus far she hasn’t

been expelled from the church, and she doesn’t expect it to happen. But

if that day ever comes, she plans to study the disputed doctrines one more

time, to consult with her trusted colleagues, to pray, and then to

"have the courage of what I think it means to be a Catholic -- to say

what I believe. And let the chips fall where they may." The Many True

Faiths If that’s a

Catholic sentiment, it’s one more at home in pluralist America than in,

say, late-15th-century Spain. The rise of secular liberties has made it

much easier to discard all or part of your faith without earthly

repercussion, especially during the last century. At the same time,

revolutions in communication and transportation have made it easier than

ever to sample the planet’s spiritual cuisines. A hundred and fifty

years ago, an American could live his entire life without learning that

Buddhism existed. Fifty years ago, in most of the country, he had to make

a special effort to track down the details of Buddhist doctrine. Today, he

can type a few words into a search engine and discover a host of Buddhisms,

some more authentic than others. If Kissling

represents the first trend, then the second is embodied in Zalman

Schachter-Shalomi, a Jew born in Austria and based today in Boulder,

Colorado. The 78-year-old founder of the Alliance for Jewish Renewal is

not merely a Hassidic rabbi but an initiated Sufi sheik; he has explored

traditions ranging from Buddhism to voodoo, from Native American peyote

rituals to the Baptist church. "In Judaism, we believe the messiah

has not come yet," he says. "Which means we are not out of the

woods yet, you know? We cannot claim that we have the totality of truth.

Each of the religions has a fragment, and none of them has the whole

thing." This universalist

idea is hardly new. The Sufi philosopher Hazrat Inayat Khan, for one,

argued a century ago that all the world’s faiths shared a common truth.

("We need not give up our religion," he once wrote, "but we

must embrace all religions in order to make the sacredness of religion

perfect.") In 1923 Inayat initiated the Jewish-born Samuel Lewis,

known to his followers as "Sufi Sam," who by that point was

already well along a philosophical road whose stops ranged from Theosophy

to Zen to General Semantics. It was Lewis, in turn, who initiated

Schachter-Shalomi into Sufism. By that point, the rabbi had been venturing

into other faiths for years. Lewis’ brand of

Sufism does not claim to be Islamic. Schachter-Shalomi, by contrast, has

never given up his Jewish roots. His explorations were meant not to

replace the For all that, the

rabbi doesn’t entirely dismiss the traditionalist critique of the

spiritual cafeteria. In the late ’60s, when he sometimes taught in the

San Francisco Bay area, he noticed that "people would say they were

‘into’ this now, and then they would get ‘into’ that, and each

time they were looking for that honeymoon period with a new

discipline." He corrects himself: "Not discipline -- a new tradition.

When it came to discipline, they’d opt out and then go to the next one.

Because they wanted a hit." The difference

between them and him, he argues, is that "I didn’t step out of

Judaism to become a practicing something-else. But when I get in touch

with another From Pluralism

to Paganism If Kissling and

Schachter-Shalomi seem avant-garde, it’s only because they’ve thought

through their positions with more rigor. If there aren’t many Catholics

with a detailed theological argument for abortion rights, there are plenty

who break with their faith on that or some other important issue. And if

Schachter-Shalomi’s universalism is unusual, his willingness to explore

rival confessions is not. Writing in The Wall Street Journal in

1999, Lisa Miller described not only the rabbi who became a Sufi sheik but

a "Christian Buddhist, but sort of tongue-in-cheek," plus a

Jewish/Buddhist cross-over that’s "become so commonplace that

marketers who sell spiritual books, videotapes and lecture series have a

name for it: ‘JewBu.’" Within the Unitarian Church, there are

organi-zations of Unitarian Buddhists and even Unitarian Pagans. Neopagans

themselves mix all sorts of spiritual ingredients -- and not always

consciously. Many carry baggage from the churches they’ve supposedly

rejected. "The former Catholics are the ones that are into the big

ceremonial magic, because that’s what they grew up with -- the big

Catholic ceremonies," argues Ceredwyn Alexander, a 33-year-old pagan

(and former Catholic) who lives in Middlebury, Vermont. "And the

Baptist pagans tend to be the rule-oriented pagans: ‘You must be

facing the east at this particular time of day, and anything other than

that is evil and wrong!’"

|

Not every neopagan is as rigid as that. Indeed, neopaganism is almost unique among the world’s faiths for its adherents’ willingness not just to adopt radically new beliefs or practices but to jettison ideas that once stood at the center of the pagan worldview. Paganism in the broadest sense goes back to the Stone Age, but neopaganism is a product of the last 100 years, born when various mystics, most notably the English occultist Gerald Gardner, assembled new spiritual movements out of several preexisting social currents, from Freemasonry to woodcraft groups. Gardner claimed he had inherited his species of witchcraft, initially dubbed "Wica," from an unbroken chain of transmission that dated back to pre-Christian times, was kept alive in secret, and resurfaced publicly only after the U.K. repealed its anti-witchcraft statute in 1951. There are still some people who believe parts of that tale, but it is pretty well established by now that Wicca was Gardner’s own invention. This point is

much less controversial in pagan circles than you might imagine. Two years

ago, Charlotte Allen wrote an article for The Atlantic that was

positively breathless in debunking Wicca’s creation myths: that Gardner

had revealed a long-established secret religion, that it could be traced

back to a primeval goddess cult that once covered all of Europe, that the

Christian witch hunts were launched to eradicate that ancient order, that

this persecution was a holocaust that claimed 9 million women’s lives.

As Allen noted, the case for an overarching goddess-worshipping ur-faith

has been severely weakened in recent years, while the rest of the story is

in even worse shape: The figure of 9 million dead women is simply untrue,

as is the notion of a witchy secret society that spent centuries

underground. How was Allen’s

article received? For the most part, to judge from the letters The

Atlantic printed, with a been-there-done-that shrug. Toward the end of

the piece, That was an

understatement. Pagan fundamentalists who insist their religion is

centuries old certainly exist, but even in the 1970s mavericks such as

Isaac Bonewitz, the Berkeley-based Druid, made a point of arguing that the

Wiccan origin story was inaccurate. Margot Adler’s Drawing Down the

Moon (1979), one of the books that did the most to introduce Americans

to neopaganism, frankly declared that until recently, most Wiccans

"took almost all elements of the myth literally. Few do so today,

which in itself is a lesson in the flexibility of the revival." Adler’s book,

incidentally, is one of the best on the topic, surpassed only by the

British historian Ronald Hutton’s The Triumph of the Moon (1999).

But while Adler’s tome is good journalism, it isn’t exactly objective.

The author is a practicing pagan herself, and her book has an agenda,

which Hutton summarized well: "She recognized that Wicca had probably

been built upon a pseudo-history, and then suggested that this was normal

for the development of religious traditions and that Wiccans deserved

credit for the fact that they were increasingly conscious of this without

losing a sense of the viability of their actual experience of the divine.

What emerged from Drawing Down the Moon was an argument for modern

paganisms as ideal religions for a pluralist culture, and for witchcraft

as one of these." Because it was so widely read, Adler’s book ended

up not just highlighting this interpretation of modern paganism, but

spreading it. Odin, Buddha,

Allah Such pluralism

allows pagans to take ecumenicalism even further than Rabbi

Schachter-Shalomi does. Jim Davis, a 43-year-old man in Springfield,

Missouri, practices Asatru, a revival of Viking mythology. He is,

simultaneously, a Buddhist and something of a Muslim, though his heretical

"edge Islam" wouldn’t go over very well in Mecca. "I

don’t actually combine them," he says of his three faiths. "I

just hold all three at the same time." Davis was raised

a Southern Baptist; when he got fed up with that, he became an atheist.

After some apparently mystical experiences restirred his interest in the

spiritual, he started investigating the other religions of the world,

settling initially on Buddhism "because I found it the least

objectionable, from an atheist background." When he learned that some

Buddhist sects had imported older Asian deities into their faith,

reimagining them as protector spirits or as personified Bodhisattvas, he

wondered why he couldn’t do the same with Western mythologies. Again he

began searching, this time for an appropriate set of spirits. The Norse

gods -- Thor, Odin, Freya -- seemed to be a good fit. "I started

seeing them as Buddhist protectors," he recalls. "But I

wouldn’t tell my Asatru friends that." Today, years

later, Davis is less interested in fusing one faith with the other.

"That’s how I first justified it," he explains, "but now

I think Buddhism has its own system, and you have to be true to it for it

to work for you." The religions fill different needs in his life, so

he keeps them in separate boxes: Asatru lets him be part of a spiritual

community with its own collective rituals, while Buddhism is something he

does by himself. And Islam? Davis

discovered it through Peter Lamborn Wilson’s 1988 book Scandal:

Essays in Islamic Heresy, which isn’t exactly your standard romp

through the It’s a personal

path, like his Buddhism -- it’s just that he pursues one with discipline

and the other with a deliberate disregard for it. "The idea

that you have to have one faith smacks of monotheism," he complains.

"It’s like you’re just practicing Christianity in a pagan form. I

think the true meaning of polytheism is not so much the belief in more

than one god but holding more than one worldview at the same time."

It helps that he doesn’t take the religions literally, preferring to

regard them "as powerful metaphors that you could either read meaning

into or derive meaning from. Of course, sometimes those metaphors take on

lives of their own." In Triumph of

the Moon, Hutton argues that neopaganism is eclectic and protean. It

is not just capable of adopting ideas -- gods, rituals, creeds -- from

many different sources but is remarkably adaptable itself, allowing very

different people to refashion it in their own images. This is true of all

long-lived religions, of course, but in this case the evolution has

occurred at a stunning pace. Consider

paganism’s political dimensions. In Modern Witchcraft (1970), the

journalist Frank Smyth observed that the British witches he interviewed

tended to be politically conservative. So, Hutton notes, did the founders

of the movement, and the figures who influenced them. But in the ’60s

and ’70s -- first in America, but soon in Britain as well -- the

religion was altered by feminist and environmentalist currents; in America

especially, Wicca was often associated with the political left. The new

collection Modern Pagans (2002), an anthology of interviews by V.

Vale and John Sulak, reveals a subculture that would have been a bracing

surprise to the neopagans of 50 years ago: goths, gay activists,

anti-globalization protesters, a cyberspace-based "technopagan,"

even a Buddhist Beat poet. It is the

protean, adaptive quality Hutton identified that allowed these new

variations to emerge. When feminists discovered paganism, they were

attracted to the idea of goddess worship, and to the implications of a

matriarchal past; the Wicca they then developed was very different from

the one Gardner created. Green pagans, meanwhile, turned to

"Earth-based spirituality" -- and in the process, Hutton notes,

they transformed fertility rites into nature worship. Libertarian pagans

enjoyed the Millian overtones of Wicca’s central ethical principle:

"An it harm none, do as ye will." Even the radical right found a

niche by imposing a racialist gloss onto Asatru, to the discomfort of

anti-racist Odinists such as Davis. As one moves

further from the Wiccan mainstream, neopaganism’s eclectic quality --

its status as a religion of appropriation -- becomes yet more obvious. The

Church of Aphrodite, founded on Long Island in 1938, was inspired by the

myths of classical Greece as viewed through the lens of one Russian émigré’s

mind. Subsequent neopagans took their inspiration from the Druids, from

ancient Egypt, from the Vikings, from Rome. Others looked to traditions

that survived to the present day: to African animism, to Santeria and

voodoo, to American Indian religions, even to Hinduism. Inspiration does

not mean perfect reconstruction. There is a sometimes dramatic difference

between those in the original tradition and those appropriating it for

their own purposes -- between an ordinary Hindu, for example, and an

American witch who has added the goddess Kali to her personal pantheon.

One devotee of the Egyptian gods told Adler that he was a Jungian and that

his deities "represent constructs -- personifications." Some

pagans would leave it at that; others, including Adler’s interviewee,

would insist that on the other side of those interpretive constructs are

forces with an independent existence. Either way, it’s a far cry from

mainstream Hindu theology. Some pagans

prefer to create their pantheons from thin air. A witch named Deborah

Cooper has created a Temple of Elvis, identifying the king of rock ’n’

roll as the Horned God; in Modern Pagans, she declares:

"I’ve seen many writings correlating Elvis and Jesus, but I don’t

think he’s very Jesus-like. I think it’s good for us Pagans to reclaim

him as ours." One of the better-known pagan sects grew out of a

reading group devoted to Ayn Rand, Abraham Maslow, and Robert Heinlein.

The latter’s novel Stranger in a Strange Land (1961) included a

Church of All Worlds, whose founder was raised by Martians and whose

followers practiced communal living and free love. With time, a real

Church of All Worlds was born, with all the above elements except the

origins on Mars. Its philosophy fused pantheism, ecology, and

anti-authoritarian politics, without ever shedding its ties to science

fiction. It was only a

matter of time before someone started mixing frankly fictional characters

with the deities of older traditions. If your pantheon consists of

cultural archetypes rather than literal beings with continuous histories,

why exclude the creations of J.R.R. Tolkien, Marvel Comics, and Madison

Avenue? If you can treat your religion like art, couldn’t you also treat

your art like religion? So it was that in

1993 members of the Order of the Red Grail, a Wiccan group in Nebraska,

held an "experimental magickal working from the High Elven point of

view," drawing on the world invented by Tolkien. And so it was that

in the mid-’80s some occultists in California -- not a pagan group, my

informant stresses, though there were some pagans among them -- attempted

to channel the Amazing Spider-Man. The collective unconscious was probed,

and a persona claiming to be Peter Parker emerged; the magicians then

tested the alleged superhero by asking what would take place in the next

few issues of the comic book. Alas, the channeler’s predictions proved

inaccurate, thus nipping the project in the bud. Spiritual

Jacuzzi Which brings us

back to the Hot Tub Mystery Religion. "It was kind of an impromptu

phenomenon," says Yehoodi Aydt, 39. "About 1991 or ’92,

several of us got together as sort of an affinity group, and we started

doing events and parties and installations and putting out zines and

whatnot. And it kind of evolved into a mystery religion." One of the

group’s early inspirations was Alexander Scriabin, a Russian composer of

the late 19th and early 20th centuries who dreamed of creating a work of

art that would occupy every sense, driving the audience into a

transcendental state. (The piece, called "The Mysterium," was to

be performed in a specially built cathedral in India. It required, among

other elements, "an orchestra, a large mixed choir, an instrument

with visual effects, dancers, a procession, incense, and rhythmic textural

articulation" -- not to mention bells suspended from zeppelins.) The

Hot Tub group’s installations combined music, visual art, food, and

sometimes mind-altering chemicals, along with symbols from Sufism, the

Cabala, and other sources. Aydt participated in an annual Halloween event

called the Disturbathon, which existed somewhere in the hazy territory

between performance art and a haunted house. "It involved nudism in a

maze-like environment," he recalls, "and there was inevitably

some kind of pit." Sometimes the Hot

Tubbists rented big warehouses for the events; other times, they met in an

apartment in Euless, Texas. Eventually, Aydt recalls, "It got to the

point where our mutual goal was to provide a spontaneously occurring

initiatory experience. It went from being an accidental, ‘Hey, we all

got together and something very strange happened’ situation to a more

planned, ‘Well, if we play our cards right and do certain things, we can

induce this same kind of group experience.’" And so a new religion,

devoted to "monotheist pagan mysterianism," was born. Such playfulness

marks the so-called Free Religions. Under this header one finds

Discordianism, the "Non-Prophet Irreligious Disorganization"

devoted to the Greco-Roman goddess of disorder; the Church of the

SubGenius, inspired not by classical mythology but by conspiracy theories,

UFO cults, and sales manuals; and the Moorish Orthodox Church, which might

best be described as Discordianism crossed with Afro-American Islam. Other

Free Religions are one-off efforts, sometimes launched by followers of

other free faiths. The Discordian filmmaker Antero Alli, for example, has

invented a spiritual practice centered around Fred Mertz, Ethel’s

husband on I Love Lucy. Mertz, he argues, was a Bodhisattva, master

of "such sophisticated techniques as Senseless Bickering, Scathing

Indifference, Bad Timing, Advanced Balding and the Five Secrets of

Stinginess." There is, or was, a First Arachnid Church whose deadpan

tracts honor "the Great Spider and the True Web," and there’s

probably a similar church out there devoted to the Great Pumpkin, though I

haven’t been able to locate it yet. On one level, of

course, these are parodies, and some of them don’t aspire to be more

than that. But there’s more to the Free Religions than satire. The Hot

Tub group, which drew heavily on both Discordianism and Moorish Science,

was in no sense unserious in its efforts to reach a transcendental state.

For the Discordians, the wisecracks are there, in part, as a defense

against fundamentalism. The theory is that religious texts are metaphors

at best, that some of the world’s most hazardous social conflicts began

because people took those metaphors literally, and that one way to

overcome this is to develop a doctrine so absurd that no one could

possibly take it at face value. If religion is art, then this is spiritual

dada. In a way, none of

this is unusual. There have always been people who discard the elements of

their faith that they dislike, and there have always been syncretic

religions that fuse one spiritual system with another. What is new is the

ease of the former, the speed of the latter, and the extent to which the

two have combined. There is a wide

gulf, of course, between someone who merely fine-tunes her Catholicism and

someone who replaces the Virgin Mary with the goddess of chaos; between a

Jew who mixes milk with meat and a Jew who practices witchcraft. If I am

describing a trend, it is one that covers a wide spectrum of behavior,

from the ordinary to the outré. As a journalist, I have naturally focused

on the latter -- but it’s the former, obviously, that is reshaping

society. The question then

becomes how adaptable these re-vised and reinvented faiths will be in the

long haul. Rabbi Schachter-Shalomi notes that one function of religious

ritual is to bind the generations, and that it’s not clear how useful

the new combinations are in that regard. "Most of the people who are

inventing these things de novo will not have a second

generation," he warns. "They wanted to get the highs out of the

individual practice, but they don’t do things in the household and

families." That doesn’t

mean that the spiritual cafeteria itself will inevitably collapse. More

likely, the next generation will invent, reinvent, and rediscover its own

religious practices, just as its parents are doing now. Associate Editor Jesse Walker is the author of Rebels on the Air: An Alternative History of Radio in America (NYU Press).

|

|

Haiti

officially sanctions Voodoo By

MICHAEL NORTON, Associated Press Writer PORT-AU-PRINCE,

Haiti - Haiti’s government has officially sanctioned voodoo as a religion,

allowing practitioners to begin performing ceremonies from baptisms to

marriages with legal authority. Many who practise

voodoo praised the move, but said much remains to be done to make up for

centuries of ridicule and persecution in the Caribbean country and abroad. Voodoo priest

Philippe Castera said he hopes the government’s decree is more than an

effort to win popularity amid economic and political troubles. “In spite

of our contribution to Haitian culture, we are still misunderstood and

despised,” said Castera, 48. In an executive

decree issued last week, President Jean-Bertrand Aristide invited voodoo

adherents and organizations to register with the Ministry of Religious

Affairs. After swearing an

oath before a civil judge, practitioners will be able to legally conduct

ceremonies such as marriages and baptisms, the decree said. Aristide, a

former Roman Catholic priest, has said he recognizes voodoo as a religion

like any other, and a voodoo priestess bestowed a presidential sash on him

at his first inauguration in 1991. “ An ancestral

religion, voodoo is an essential part of national identity,” and its

institutions “represent a considerable portion” of Haiti’s 8.3 million

people, Aristide said in the decree.

|

Voodoo

practitioners believe in a supreme God and spirits who link the human with

the divine. The spirits are summoned by offerings that include everything

from rum to roosters. Though permitted by Haiti’s 1987 constitution, which recognizes religious equality, many books and films have sensationalized voodoo as black magic, based on animal and human sacrifices to summon zombies and evil spirits. “It will take

more than a government decree to undo all that malevolence,” Castera said,

and suggested that construction of a central voodoo temple would “turn

good words into a good deed.” There are no

reliable statistics on the number of adherents, but millions in Haiti place

faith in voodoo. The religion evolved from West African beliefs and

developed further among slaves in the Caribbean who adopted elements of

Catholicism. Voodoo is an

inseparable part of Haitian art, literature, music and film. Hymns are

played on the radio and voodoo ceremonies are broadcast on television along

with Christian services. But for centuries

voodoo has been looked down upon as little more than superstition, and at

times, has been the victim of ferocious persecution. A campaign led by the

Catholic church in the 1940s led to the destruction of temples and sacred

objects. In 1986, following the fall of Jean-Claude Duvalier’s dictatorship, hundreds of voodoo practitioners were killed on the pretext that they had been accomplices to Duvalier’s abuses.

|